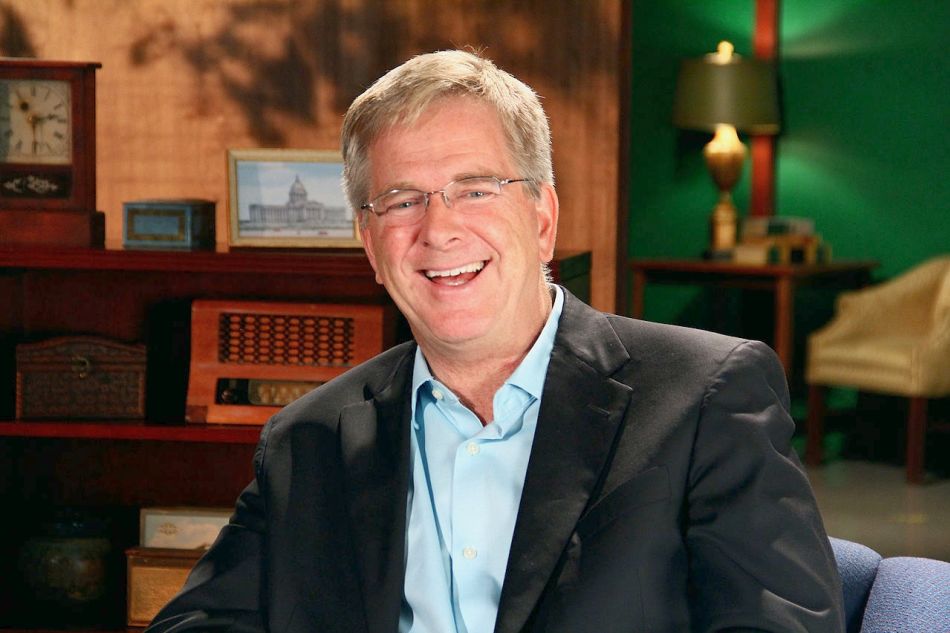

Rick Steves: Using Travel to Better the World

Greggory Moore | Best of Best

image by: Carlos Manzano

“Keep on travelin’,” he says at the end of most of his travelogues. But for Rick Steves, it’s a catchphrase that is no less about self-betterment than sightseeing. And he walks the walk.

If you watch PBS, you know Rick Steves. He’s that blond, bespectacled fellow with the Mr. Rogers delivery who takes us on travels throughout Europe and beyond, showing us sights, sharing history, and providing practical travel tips. He is probably America’s most famous traveler, and he’s become enough of a staple of PBS programming to be a regular feature of every pledge drive.

But Steves is not content merely to show us the world. Traveling may be his job, but he works it partly to bring people together through exposure to each other; and he uses his success to improve the world around him.

The Rick Steves story starts out as both ambitious and modest. Having acquired a wanderlust at 14 when he accompanied his father on a business trip, at 18 he was funding his solo travels with his earnings as a piano teacher. Just one year later, in 1976, he started Rick Steves’ Europe as a one-man endeavor. In 1980 he published the first edition of travel guide Europe Through the Back Door, with its dual foci of getting the most bang for your buck and enjoying an authentic local (as opposed to a travel industry) experience. Two years later he was giving three-week minibus tours. Way led to way, and by 1990 he had produced three seasons of Travels in Europe with Rick Steves for public television.

Even early on, Steves saw traveling abroad as a means to bring the world closer together. “Globetrotting destroys ethnocentricity,” he says. “It helps you understand and appreciate different cultures. Travel changes people. It broadens perspectives and teaches new ways to measure quality of life. Many travelers toss aside their hometown blinders. Their prized souvenirs are the strands of different cultures they decide to knit into their own character.”

He also saw it as a means to help Americans stop seeing ourselves as the center of the world. “Our Earth is home to nearly 6 billion equally important people,” he wrote before the world population surpassed that number. “It's humbling to travel and find that people don't envy Americans. Europeans like us, but with all due respect, they wouldn't trade passports. […] Give a culture the benefit of your open mind. See things as different but not better or worse. […] Travel is addicting. It can make you a happier American, as well as a citizen of the world.”

Even at the beginning of his career, Steves aimed to raise the consciousness of his fellow travelers. “In my earliest days as a tour guide, I'd put people in terrible rooms just so they would better appreciate having a nice home as their norm,” he says. “I'd intentionally not have a hotel reservation for my groups until late in the afternoon...just to put my tourists through the anxiety of not knowing if they'd have a roof over their heads tonight. The intended souvenir: more empathy for the homeless.”

Although this approach was short-lived, it was a foretaste of Steves’s lifelong concern over economic injustice, which he sees as a main theme of his Christianity. “I really believe that the Bible is concerned about economic justice,” he told U.S. Catholic in 2011. […] I’m haunted by the fact that good Christian Americans vote only for their own short-term financial and material interest. […] Americans read the Bible in a way that makes us feel good without dealing with the reality that we ignore the desperately poor. Jesus cared about the poor and said some pretty harsh things about economic justice. […] If people are just motivated by greed and have no personal faith at all, that’s their own problem, but many Christians need a caring but straight-talking friend to explain economic justice issues to them.”

Steves’s straight-talking includes calling the election of Donald Trump a bellwether of “the rise of a new, greed-is-good ethic in our government.” But rather than “just complaining about how our society is once again embracing ‘trickle-down’ ethics, and our remarkable ability to ignore the need in our communities even as so much wealth is accumulated within the top one percent of our populace,” Steves puts his money where his mouth is. “Twenty years ago, I devised a scheme where I could put my retirement savings not into a bank to get interest, but into cheap apartments to house struggling neighbors,” he says. “[…] Rather than collecting rent, my ‘income’ would be the joy of housing otherwise desperate people. I found this a creative, compassionate and more enlightened way to ‘invest’ while retaining my long-term security. This project evolved until, eventually, I owned a 24-unit apartment complex, the use of which I provided to the YWCA. They used it to house single moms who were recovering hard-drug addicts and were now ready to get custody of their children back.”

Originally Steves’s commitment to the YWCA was only 15 years, after which he could (if need be) take back control of the complex—which, after all, was his retirement nest egg—although his hope was that he would be do well enough financially to bequeath it to the YWCA. But Steves altered the plan in response to Trump’s election: “[I]nspired by what's happening in our government, and in an attempt to make a difference, I decided to take my personal affordable housing project one step further: In 2017, I gave my 24-unit apartment complex to the YWCA. Now the YWCA can plan into the future knowing this facility is theirs.”

This level of social consciousness is par for the course for the man who in 2009 published Travel as a Political Act, which in 2017 was updated (for the second time) to touch on topics such as “the impacts of Donald Trump in the U.S., Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, the refugee crisis, fascism and nativism, 'fake news,' and Brexit."

That Steves would eventually publish a book touching upon such topics was presaged by more modest implementations of his brand. In 1999 and 2000, for example, he placed full-page ads in his guidebooks to raise awareness of the Jubilee 2000 campaign, which encouraged the First World to extend debt forgiveness to developing nations. In 2008 he used Rick Steves’ Europe to distribute his tour through Iran, which he has made a point of posting in full on his website. Intermixed with the sites and sounds of the former Persian Empire is not a little bit of contemporary history, including the roots of why the Iranian government feels so antagonistic toward the United States. Steves goes as far as to speak with several Iranians about how they personally feel about Americans, revealing that, in contrast with the stereotypes many Americans have about the Iranian people, the average Iranian on the street does not wish “death to America.”

Domestically, one of Steves’s earliest causes was the legalization of marijuana. He started speaking out in the late 1980s—although at first he did so anonymously. “ Back then, it felt risky to use my own name when talking drug policy,” he recalls. But in the early 2000s he was out publicly. "I was frustrated 10–15 years ago,” he told Civilized last year. “This is an important issue but people who agreed that it would be pragmatic and wise to stop the war on marijuana were afraid to speak out because it would hurt their business, or it would hurt their political prospects, or it would hurt their standing socially. And I'm unique in that I don't need to be elected and that I'm my own boss—nobody can fire me, and I'm not a publicly held company.”

True to form, Steves did more than simply talk about the issue. In 2003 he joined the board of directors of NORML (National Organization to Reform Marijuana Law), and he took in active hand in pushing for legalization on the West Coast (including his home state of Washington). Once legalization took hold there, he turned his attention to the East Coast, not only going to Massachusetts and Maine to campaign for ballot initiatives there, but pledging $50,000 of his own money in matching donations for the latter.

Steves’s attitude toward marijuana and America’s War on Drugs has been shaped by—what else?—his experience of other cultures. “[T]he US criminalization of marijuana drains precious resources, clogs our legal system, and distracts law enforcement attention from more pressing safety concerns,” he writes in Travel as a Political Act. “[…] It’s interesting to compare European use to the situation back home, where marijuana laws are strictly enforced. According to Forbes Magazine, 25 million Americans currently use marijuana (federal statistics indicate that one in three Americans has used marijuana at some point), which makes it a $113 billion untaxed industry in our country. The FBI reports that about 40 percent of the roughly 1.8 million annual drug arrests in the US are for marijuana—the vast majority (89 percent) for simple possession...that means users, not dealers. […] Like my European friends, I believe we can adopt a pragmatic policy toward both marijuana and hard drugs, with a focus on harm reduction and public health, rather than tough-talking but counterproductive criminalization. The time has come to have an honest discussion about our drug laws and their effectiveness.”

Many Rick Steves’ Europe episodes get a telling tagline just as they conclude: This program is brought to you in part by a passion for a better understanding of the world. Steves believes that through such understanding we become better and more compassionate people, increasingly united across cultures by our common humanity. And there may be no better example of such an ethos than Rick Steves himself.

About the Author:

Except for a four-month sojourn in Comoros (a small island nation near the northwest of Madagascar), Greggory Moore has lived his entire life in Southern California. Currently he resides in Long Beach, CA, where he engages in a variety of activities, including playing in the band MOVE, performing as a member of RIOTstage, and, of course, writing.

His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, OC Weekly, Daily Kos, the Long Beach Post, Random Lengths News, The District Weekly, GreaterLongBeach.com, and a variety of academic and literary journals. HIs first novel, The Use of Regret, was published in 2011, and he is currently at work on his follow-up. For more information: greggorymoore.com

Introducing Stitches!

Your Path to Meaningful Connections in the World of Health and Medicine

Connect, Collaborate, and Engage!

Coming Soon - Stitches, the innovative chat app from the creators of HWN. Join meaningful conversations on health and medical topics. Share text, images, and videos seamlessly. Connect directly within HWN's topic pages and articles.